A dance of idioms, a shift of semantics: Defending the Cliché with Dr. Véronique Dudouet

By Sandy Di Yu

Like all clichés, the origins of the phrase “one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter” is shrouded in myth and echoes. While it has its uses in popular media and classroom debates, it’s a phrase that incites all sorts of abuse, from academia to random internet forums, dismissed as reductive, devoid of real substance save for the fluff of empty ideology, or else a phrase uttered only by terrorist sympathisers, heaven forbid. It’s a phrase that, despite our best efforts, forces its way into mind when Dr. Véronique Dudouet takes stage. Just as well, for if we are to believe Rancière, dismissing clichés for their own sake is itself a cliché, thus submitting us to the worst of the circulating stereotypes[1]. To this end, this article is in some respects a defence of cliché, perhaps not to ascertain it as a categorical staple but at the very least as a campaign to reassert certain clichés as valuable.

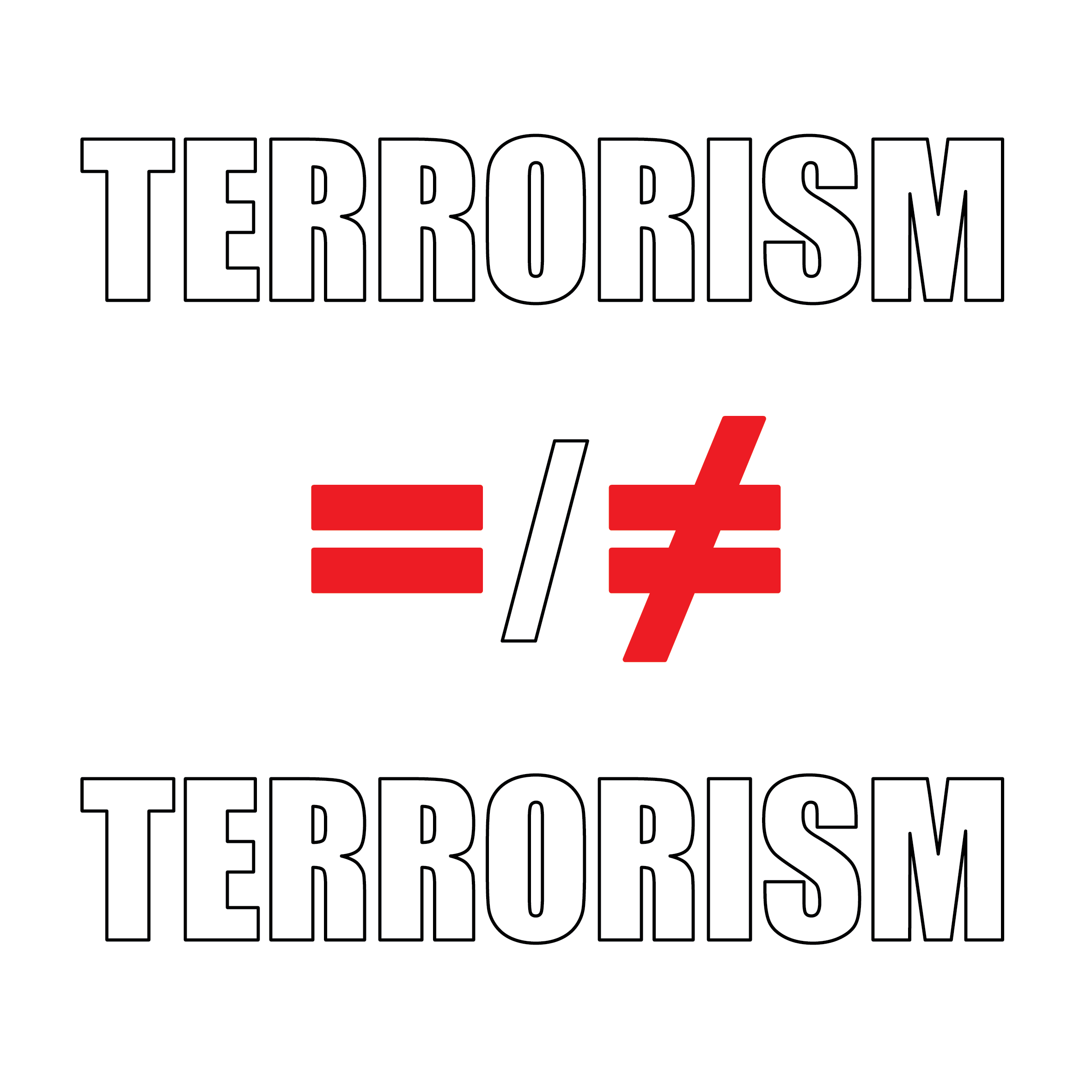

On February 12, Dr. Véronique Dudouet, the programme director for Conflict Transformation Research at the Berghof Foundation in Berlin, discussed the challenges of third-party dialogue with armed groups in our post-9/11 era at Goldsmiths, University of London. To the crowd of eager listeners, she elucidated the new frontiers being faced and the challenges to overcome in engaging armed groups. Without getting into specifics yet, if one were to sum up Dr. Dudouet’s vast library of research in simple terms and a single sentence, it may go something like this: “In order to better understand the workings of armed resistance organisations and therefore enact better policy making for the sake of conflict resolution, a thorough survey of the contextualising semantics of the groups in question is a necessary premising step.” In other words, semantics matter, and have real-world consequences on the livelihood of demographics at large. In reference to the opening idiom, we could take from this that the term “terrorism” is, in fact, subject to perspective.

The point here is that there is value in reassessing the categorisation and labelling of these groups if peace is the goal. But that’s not to say that there aren’t countless voices (all men, all with American interests[2], however you want to interpret that, if at all) ferociously deriding the cliché, as if the defence of a nation was dependent on it. One individual[3]calls the phrase a cop-out, saying that any act of violence towards civilians is necessarily a terrorist act, and any group or individual who engages in these activities, regardless of how pure in motive they are, is a terrorist. This disregard for motive is echoed throughout literature that argues against the phrase, along with the dry fact that terrorist groups are groups which do not possess statehood. We can then recognise the two pillars of the argument against the cliche as these: that motives don’t matter, and that official statehood is a determinant factor.

But not everyone dismisses the saying outright. Connor Friedersdorf of the Atlantic gives an example of how to make sense of the cliché, wherein the organisation Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK for short) was to be taken off of the official list of terrorists despite its continued acts of violence against civilians. In the months leading up to discussions of its delisting, a scientist was killed at the hands of members who planted a car bomb. But this was forgivable because the scientist in question was Iranian and the members who committed the crime were trained by Israeli secret service[4]. With Iran being alleged enemy number one of the United States, and with Israel being in bed with American politics, the terrorist organisation was officially delisted as a terrorist organisation on September 28, 2012[5].

All this is to say that the cliché is defensible, even if it’s not altogether popular in conservative circles. But the phrase “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter” is perhaps so self-evident in Dr. Dudouet’s research, or perhaps not wide enough to account for the breadth of the issues with such groups, that in a previous paper she authored, the term “terrorist” never comes into play. To take it a step further, the term widely used by the United Nations “Non-State Armed Group” (NSAG for short) is also dismissed. The reason for this comes back to the above mentioned two pillars of statehood and motive. These are also the pillars that Dr. Dudouet elegantly erodes into semantic soup, citing research through empirical observation and interviews with members and former members of several resistance movements while gently criticising existing literature on the topic.

The question of statehood has several applicable counterpoints. We might notice even prior to the research presented to us by Dr. Dudouet that there is an immediate logical fallacy in defining terrorist activity based on statehood. If a group requires sanctified statehood to be released from the label of Non-State Armed Group, terrorist group or other such names with unfavourable reputations, but if part of their motives is to become recognised as a legal state, then this is begging the question. The very reason for their resorting to extreme measures is their inability to be recognised as a nation state, which subjects them to these labels, which begets their motive. There is no way for these groups to shake the label except to stop existing. In many cases, we see legal states blocking the non-state group from accessing the possibility of statehood, again resulting in the same fallacy.

One might argue that this is so far just a continued game of semantics. Changing a group’s rank to statehood doesn’t alleviate them from consequences in committing such crimes. If legal states commit acts of terror during times of war, these acts are defined as war crimes. If a sanctioned military commits such acts during peacetime, it’s considered a crime against humanity. Any act of violence towards civilians is punishable, as is internationally agreed upon in international law[6].

While this might seem to be a simple solution out of the issue of statehood, it remains reductive. This does not consider the power dynamics between a military with state funding and a marginalised group with conflicting interests, nor does it account for the public opinion, which is influenced by labels and can influence certain actions for or against groups and militaries. Sanctioned legal militaries have a power of authority, and therefore resources (political, publicity-related and otherwise) that NSAGs do not. They have access not only to funding for weapons but funding for their very livelihoods as well as lobbying (although, as seen with the case of MEK, certain interest groups may provide funding for groups previously regarded as terrorist organisation groups). This leads to the next point, which is that motives doin fact matter. As cited in Dr. Dudouet’s 2012 paper on the issue[7]as well as her recent lecture at Goldsmiths, the label of “Non-State Armed Group” ignores an organisation’s historic work in policy, their historic claims to statehood or their future aspirations towards statehood. Many groups in question have had vast histories wherein their exact contention with the powers that be is their lack of statehood, and therefore the economic and political advantages that it comes with. These groups identify themselves as resistance or liberation movements, reflective of the motives which are overlooked by those who reject the subjective applicability of labels, by those who deny them the term “freedom fighter”, resistance group and so on.

There are seven groups that are considered in the paper including the Communist Party of Nepal - Maoist and its People's Liberation Army, the Free Aceh Movement, Sinn Féin and the Irish Republican Army, Kosovo Liberation Army, Farabundo Marti Liberation Front, 19th of April Movement, and the African National Congress. These groups are all former rebel movements, and each of these groups has undergone “successful transitions from violent insurgency to peaceful political participation, through processes of negotiation, demobilisation, disarmament, and democratic institutionalisation”[8]. While some authors might suggest that certain countries advocate for the use of the “freedom fighter” so that violence is justifiable[9], these groups would instead argue that violence was executed as a last resort. In the example of Kosovo, internal guidance was distributed in the KLA that ordered refrain from attacking civilians and socio-cultural monuments, but to commit disruptions with a just character. Sinn Féin’s definition of armed struggle proclaimed it a necessary part of a demographic’s resistance to foreign oppression. The African National Congress observed the Geneva Protocol in regards to irregular warfare.

In addition to this, members of these groups all claim large numbers of support from their societies, whether within ethnic or social constituencies, and looked to these groups as the defenders of their interests.[10]Certain federal powers of sanctioned states may have specific interest in keeping resistant groups at bay, whether by PR or otherwise, especially if by democratic election these groups may be determined to be rightfully owed power and statehood, rendering a loss of power[11]. We start to see the pattern wherein those who argue against this idiom if for more than mere feelings of groundless patriotism, do so for the sake of power and not peace.

The second aspect of the name Non-State Armed Group remains problematic for members. The fact that these groups are armed may be incidental in their being dismissed as terrorist groups, but it does not account for the amount of unarmed, nonviolent protest and policy-making activities executed, or the fact that the weapons in question are a means to an end, the end being freedom and independence from their oppressors. Taking up arms and engaging in violence is often used as a last resort. The ANC in South Africa only resorted to establishing the armed wing of its organisation following decades of peaceful protest, provoked by the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960 and a ban which prevented the organisation from peaceful operations.[12]In Ireland, following centuries of British rule and violent disregard for civil rights and the introduction of 1971’s internment without trial, members of Sinn Féin came to the conclusion that repression could only end when they took up armed struggle. In each of the seven groups researched in Dr. Duduoet’s Intra-Party Dynamics and Political Transformation, the same pattern is revealed wherein a repressive regime backs the resistance group into a corner. The two pillars of statehood and motive entwine together, with statehood often being both motive and detriment. To ignore this is to ignore institutional violence and repression faced by marginalised groups, and the power dynamics inherent in systems which sanctify some political groups over others.

Other clichés can also be defended in the name of disrupting this game of conservative lobbying and myth. “Slow and steady wins the race” comes to mind. In an example about engaging groups for the goal of conflict resolution, it has been shown that immediate disarmament may lead to further violence; that a slower and steady approach to disarmament yields quicker and safer results. Another one might be something like “sticks and stones can break my bones, but names can detract from our collective goals”. We’ve already seen how governments can readily decide to relabel a resistance group at their will with the case of MEK above. But the label “terrorist”, once applied, is difficult to remove. One such case is with the ETA in the Basque country of Spain. When the Spanish government decided to engage with the group which they had once labelled “terrorist organisation”, citizens were enraged[13]. Too many mistakenly believe that one should never negotiate with terrorists. The emotionally charged reactions that terms like “terrorism” evokes coupled with the stickiness of such labels make the saying “we do not negotiate with terrorists” incredibly detrimental to peace processes.

According to Dr. Dudouet, there has been a semantic shift in recent years wherein the term Violent Extremist Organisation (VEO for short) has overtaken the term NSAG. This proposes new difficulties in attempts to engage these organisations for the sake of conflict resolution.[14] While the closed cases of past resistance groups may find solace in knowing that the violence committed was not in vain and that their struggles have ended in peace, we can only take from them the lessons of clichés. Whether they will be applicable in dealing with the newest shift towards semantic extremism, time and continued efforts for engagement will tell.

This article was written by Sandy Di Yu and was first published on 18-06-2019.

[1]Grimwood, Tom. "The Meaning of Clichés." Diacritics, vol. 44 no. 4, 2016, pp. 90-113. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/dia.2016.0021

[2]When searching the phrase “one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter” in Google, the top search results yielded are all of articles from American publications by American authors, with the two exceptions being articles published in academic journals, both by Boaz Ganor, a scholar from Israel. In the context of the topics at hand, the United States and the State of Israel share overlapping political objectives in terms of territory, a prime impetus for the debates this article addresses.

[3]Thomas Nichols is a professor of strategy at the U.S. Naval War College, and while he claims that if the U.S. was under foreign occupation he would only plant bombs at their base and not go to their country to hold a school hostage, his is a shallow interpretation of what desperate means individuals are driven to “What Do You Think the Phrase ‘One Man's Terrorist Is Another Man's Freedom Fighter’ Means?” The Choices Program, www.choices.edu/video/what-do-you-think-the-phrase-one-mans-terrorist-is-another-mans-freedom-fighte....

[4]Friedersdorf, Conor. “Is One Man's Terrorist Another Man's Freedom Fighter?” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 16 May 2012, www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/05/is-one-mans-terrorist-another-mans-freedom-fighter/2572....

[5]“Delisting of the Mujahedin-e Khalq.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, 28 Sept. 2012, www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/other/des/266607.htm.

[6]Boaz Ganor (2002) Defining Terrorism: Is One Man's Terrorist another Man's Freedom Fighter?, Police Practice and Research, 3:4, 287-304, DOI: 10.1080/1561426022000032060

[7]Dudouet, Véronique. “Intra-Party Dynamics and the Political Transformation of Non-State Armed Groups.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence, vol. 6, no. 1, 1 May 2012, pp. 66–108., doi:10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.179.

[8]Ibid, pg. 98.

[9]Ganor, pg. 288.

[10]Douduet, pg. 99

[11]Dudouet, Véronique. “From ‘Rebels’ to ‘Violent Extremists’: Implications for Engaging Armed Groups?” 12 Feb. 2019, London, Goldsmiths, University of London.6dTae1mY48kz7lzHaY/edit

[12]Douduet, pg. 99

[13]Dudouet, 2019.

[14]Ibid.